On Monday 20th October in the year 732, a battle was fought in an area between the cities of Poitiers and Tours in what is now the country of France. At the time, and for many centuries afterwards, this battle was regarded as one of the most significant in the history of Western Europe. In recent times the importance of this fight has been downgraded somewhat. On the question of as to whether that is a totally fair re-assessment, I will return to later.

This battle is known to history as the Battle of Tours or Poitiers.

Painting of Charles Martel (not contemporary)

Possibly a picture of Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi (not contemporary)

The Kingdom of Francia had been founded by Clovis I in 496, although the Franks, a Germanic tribe, had been a major factor in the Western Roman Empire for 200 or so years by then. Francia, of course, wasn’t as large as shown on the map below in 496.

Francia and the Franks have a long and tangled history that is far too complex to describe here, as interesting as it may be.

Charles was born in 686 at a time when the power of the Merovingian dynasty of Frankish kings was fading. His father was Pepin II, mayor of the palace and duke and prince of the Franks, and the effective power behind the throne. It used to be said that Charles was illegitimate, but it was common practice for Frankish nobles to have 2 or more wives, so he was seen as a legitimate heir. Pepin died in 714, and a long struggle for the succession began between various nobles who split into two camps behind Charles on the one hand and other sons of Pepin on the other hand. Charles had built up a strong following amongst the Frankish nobles. This resulted in a civil war that lasted from 715 to 718. Again, it is a complex series of events that resulted in Charles emerging as the mayor of the palace and, therefore, effective ruler of Francia.

Europe in the year 700.

A word about ‘the mayor of the palace’. This was not a mayor in the modern sense. The title was maior palatii, meaning head of the palace. It was, originally, a sort of advisor or chancellor to the kings. However, as the power of the kings faded and their role became more and more symbolic, the mayor became the true power in, and true ruler of, Francia. It was a very similar position to that occupied later, in Japan, by the Shōgun.

Maior is also the root of the word ‘major’.

The title of Duke and Prince of the Franks was dux [et princeps] Francorum. Dux was a late Roman military rank and princeps the first, the prime figure, amongst the nobility. Essentially, a military role.

The society Charles grew up in was, of course, an agricultural one. It took the work of 8 or 9 people to feed 10 people. So about 10 – 20% of the population were free of the need to work. It would be like that for many, many centuries to come, of course. Life was very hard, as it always had been for most people and would be for a very long time to come. The wealthiest of the nobility had a standard of living well below what the poorest in Western societies would expect today. It was also a proto-feudal society. Feudalism would emerge in its most developed form in France later, but the basic structure was in place and, in many ways, had always been in place. Feudalism is a fascinating topic in its own right, for me at least, and I might write about it at another time.

Little is known about Abdul Rahman. He was the governor of al-Andalus and regarded as a very competent and efficient administrator.

The Umayyad Caliphate was the fourth Caliphate established after the death of Mohammed and greatly expanded the Islamic empire. In the year 711, they intervened in a squabble amongst Visigothic nobles of the Visigothic kingdom in Hispania (modern Spain. The old Roman province). In the year 717, they crossed the Pyrenees and the old Visigothic kingdom was no more. Hispania was renamed al-Andalus and was under Islamic control. Only one area of Spain remained unconquered, the region of Asturias in the north. This region remained unconquered protected by mountainous terrain. It was from this region that the Reconquista began later.

In southern Gaul, they quickly defeated the remaining Visigothic counts and established control over a small wedge of territory in SW Gaul ( which they named Septimania). From here they began to launch bigger and bigger raids into central Gaul, penetrating further and further. These raids plundered, chiefly, the wealthy religious institutions in the area.

The four Caliphates more or less maintained the old Byzantine administrative structure in their territories. They ruled very well in fact and, in the context of their time, were quite efficient. This, too, was, of course, an agricultural society.

Meanwhile, Charles consolidated his power in a series of wars between 718 and 732, pushing the borders of the Frankish kingdom to the east, conquering Bavaria and Alemannia. He pushed the Saxons back. He had secured the firm support of many powerful nobles and unified the Frankish kingdom. He was now the real power in the kingdom, appointing kings, controlling the treasury and making all meaningful and powerful appointments. He also built up a large army of seasoned and experienced warriors.

It was during these wars that he received the nickname ‘Martel’ (Hammer).

The Duke of Aquitaine, in the meantime, was struggling against the increasingly larger and more organised Umayyad raids into his territory. Aquitaine was, technically, a vassal of the Frankish kingdom but, during the civil wars and wars that followed it had become practically independent. Duke Odo the Great of Aquitaine managed to defeat the Umayyads at the battle of Toulouse in 721, by a surprise attack, but many defeats were inflicted upon him and he was in a desperate situation.

Finally, Odo appealed to the Franks for help, pointing out the increasing danger to the Franks from the bigger and deeper penetrations of the Umayyads into Gaul. Charles agreed to this on condition that Odo would submit to the Frankish kingdom, which he did.

For their part, the Umayyads appear to have been completely ignorant of the growing power of the Franks and also ignorant of the fact that a very capable general had appeared to the north. They were not interested in the Germanic peoples and seemed to discount them as a potential threat.

Charles raised a semi-professional army, the first professional army in western Christendom since the fall of the Western Roman Empire. He financed this by seizing the assets of wealthy churches and monasteries. He prepared to march south.

The army that he raised was semi-professional, well trained, very experienced, well equipped and well supplied. This army was not, however, well articulated in that it had no standardised unit or sub-unit organisation. Soldiers organised themselves around their particular leader in groups of varying size. It was supplemented by levies raised from the peasantry who were not so well trained and equipped. It is not known how many levy troops were a part of this army, but probably about a third.

The Franks did not use cavalry, possibly because they did not have the stirrup. Nobles rode horses but dismounted to fight. The bulk of the army was, therefore armoured heavy infantry.

The Umayyad army was professional, very well organised, well articulated with unit and sub-unit organisation. It also had an excellent logistical system. It was mainly heavy cavalry.

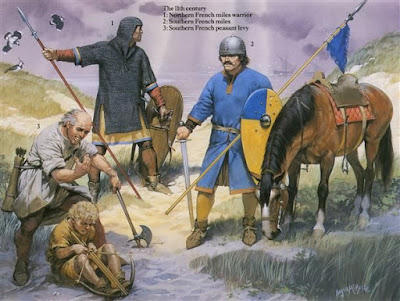

An impression of Frankish soldiers – these are from a slightly later period.

Umayyid troop types.

General impression.

The Umayyad forces advanced rapidly north, overcoming quite easily any resistance, towards the Loire valley. The army diminished in size as raiding parties were dispatched in all directions to plunder and capture slaves. The Umayyads moved so fast they outstripped their line of supply. The army was mainly heavy cavalry and the infantry core proceeded northwards slowly. Al Ghafiqi wanted to reach Tours and plunder the rich religious institution of the Abbey of Saint Martin before winter set in. He was also having supply difficulties and was slowed down by loot and captured slaves. The Umayyads were not equipped for winter and he wanted to be heading south again soon.

The Umayyad intelligence system was practically non-existent and they had no idea that a powerful Frankish army was heading south towards them. Charles moved south avoiding the Roman roads so as to screen his movements, but it would not have mattered much anyway. This enabled him to outmanoeuvre the Umayyads and deploy between Tours and Poitiers.

Charles deployment at Tours

Charles drew his army up in a solid phalanx formation in two lines. He deployed in a wooded area both to hide his true strength and to help break up the heavy cavalry charges of the Umayyads. His flanks rested on rivers and it was an excellent defensive position. It is difficult to be precise about the scale of the map above. If Charles had 20,000 troops, which is the most widely agreed figure, and drew up in two lines and we assume each line was 10,000 men, then the front was somewhere between 1,000 and 1,500 metres long, depending upon the depth of his formation.

Al Ghafiqi arrived on the scene somewhere around the 2nd or 3rd of October. He was surprised to find a Frankish army sitting across the road to Tours in a very good defensive position. The majority of his army was away raiding and he hurriedly recalled it. Charles did not want to abandon his excellent position, so the two armies faced each other for 7 days with only a little skirmishing, possibly as the Umayyads tried to scout and discover a better picture of Frankish numbers. The exact number of Franks worried Al Ghafiqi and he wasn’t very keen to attack either. However, he had to act soon as winter was drawing on and he was running out of supplies.

When the raiding parties had returned and his army was back to strength, he attacked the Franks on the 10th of October.

The Umayyads, as noted, were basically an army of heavy cavalry with an infantry component. The battle became a series of charges into the Frankish formation. How long this lasted is hard to tell. The Frankish chronicles say a day and the Arab writers say two days, which may include the retreat and pursuit of the Umayyads. However, it is likely to have been for a few hours, with perhaps quite interludes between charges. This is speculation based on other Medieval battles. The woodland helped to break up the cavalry charges somewhat and the Franks held their ground, although the Umayyads did break through the first line more than once, but were repulsed by the second Frankish line.

It would be hard grinding physical, and bloody, work.

An Arabic chronicler wrote of the Franks:

“And in the shock of battle the men of the North seemed like a sea that cannot be moved. Firmly they stood, one close to another, forming as it were a bulwark of ice; and with great blows of their swords they hewed down the Arabs. Drawn up in a band around their chief, the people of the Austrasians carried all before them. Their tireless hands drove their swords down to the breasts [of the foe]”

Mozarabic Chronicle of 754

At some point, a Frankish raiding or scouting party attacked the Umayyad camp well behind the Umayyad lines. Whether this party had been sent out by Charles is unknown. They successfully captured the camp, driving the Umayyad guards out. They began to recover some of the loot and freed the slaves that had been captured by the Arab raiders.

News of this raid reached the main army engaged with the Franks and many of the Umayyad units abandoned the battle and returned to their camp, intent on recovering their loot. They did succeed in recapturing the camp.

However, the effect of this apparent retreat by so many units affected the morale of the remaining units. They thought that a retreat was happening, so they began to fall back. This became a general retreat.

The Franks were left holding the field, probably the only time in Medieval history that an army of infantry defeated a force of heavy cavalry.

Al Ghafiqi, attempting to stop the retreat, was killed.

The Franks remained in place all night and expected a renewed attack the next day. When no attack developed Charles remained in position as he feared an attempt by the enemy to lure him out from his defensive position and ambush his forces. Scouts were sent out and they found the enemy camp abandoned and it became clear that the enemy had retreated during the night.

The battle was over and Charles Martel and the Franks had won a decisive victory.

Simple and highly schematic diagram of the battle

The Umayyads fell back to southern Gaul, and Charles continued to wage war against them for several years. It is likely that he had realised what a real threat they presented. He consolidated his hold over most of southern Gaul, bringing it into the Frankish kingdom.

In 735 the new governor of al-Andalus, Uqba b. Al-Hajjaj launched another, larger, attack against central Gaul. The Umayyads raided on a very large scale into central Gaul from 735 to 739, and a series of campaigns were fought against them by Charles. Even though Charles successfully pushed into Septimania on two occasions he was repulsed each time.

Charles died in 741 and his son Pepin the Short (714 – 768) continued the war against the Umayyads. Pepin succeeded in pushing the Umayyads once and for all out of Gaul.

Pepin’s son, and Charle’s grandson, Charlemagne (742 – 814) pushed across the Pyrenees, forcing the Umayyads back, and established Marca Hispanica in part of what is today Catalonia. This functioned as a buffer zone between the Franks and the Umayyads. Girona was reconquered in 785 and Barcelona in 801. Charlemagne is seen as launching what was later called the Reconquista.

It had taken from 732 to the end of the century to eject the Islamic presence once and for all.

The Umayyads, meanwhile, had been suffering internal conflicts which later turned into civil war and the collapse of the Caliphate.

For many centuries the battle of Tours was regarded as the decisive battle in Western Christendom, saving civilisation from Islamic conquest. It was certainly regarded as such at the time. Many modern historians have modified that view by arguing that the force stopped at Tours was only a large raiding party and not an army of conquest. It had also outrun its logistical system and was aware that winter was approaching, for which they were not prepared. Therefore, the intention was not conquest, but plunder and they would have withdrawn again anyway. They also point out that the growing internal division within the caliphate, that eventually led to civil war, made the mounting of large-scale operations into Gaul less and less likely.

This is true.

However, I would argue that the battle of Tours was the beginning of a process that led to the eventual expulsion of Islamic power from Gaul and, a long way in the future, from Spain itself. I would also argue that this battle forced Charles and the Franks to realise that there was a real threat from the caliphate and this drove him to maintain the pressure on it. It, of course, also gave him the opportunity to consolidate his control of all of Gaul.

It may, also, have functioned as a signal, a ‘wake up call’, to other powers in Western Europe.

It also, I believe, taught the Umayyads a hard lesson in exactly what they were facing in the north.

In that sense, the battle was significant and important to the defence of Western culture and civilisation, although maybe not as major as was once claimed.

Two modern historians sum this up well:

"Recent scholars have suggested Poitiers, so poorly recorded in contemporary sources, was a mere raid and thus a construct of western mythmaking or that a Muslim victory might have been preferable to continued Frankish dominance. What is clear is that Poitiers marked a general continuance of the successful defence of Europe, (from the Muslims). Flush from the victory at Tours, Charles Martel went on to clear southern France from Islamic attackers for decades, unify the warring kingdoms into the foundations of the Carolingian Empire, and ensure ready and reliable troops from local estates."

Victor Davis Hanson - Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power. Anchor Books, 2001.

"whether Charles Martel saved Europe for Christianity is a matter of some debate. What is sure, however, is that his victory ensured that the Franks would dominate Gaul for more than a century." Davis writes, "Moslem defeat ended the Moslems' threat to western Europe, and Frankish victory established the Franks as the dominant population in western Europe, establishing the dynasty that led to Charlemagne."

Paul Davis - 100 Decisive Battles From Ancient Times to the Present. Santa Barbara, California, 1999.

However, from the perspective of the current situation in Europe, I think that if Charles ‘the Hammer’ and his army could see what is happening today they would shake their heads and mutter ‘Was it worth it?’ before sadly fading away.

Si vis pacem, para bellum

¤

Islam delenda est

No comments:

Post a Comment